Making Project Planning Have Value

Tips for good project planning

I hate working on badly planned projects. It’s just miserable trying to do the impossible by working long hours, and beating myself up, just because someone didn’t take the time to add in schedule margin or understand that parts are sometimes long lead. However, having worked enough projects (good and bad) as a hardware engineer and project manager, I now have a decent sense of how long things actually take. This has enabled me to plan projects really well, and in a way that avoids most of the slog and pain. Here’s how you can do it successfully too.

A good project plan can be used to predict schedule, workload, cost, and assess risks ahead. Once you have that, the project manager can step back into a supporting role, troubleshooting problems to make sure your team has all the resources they need to do the work.

“Plans are worthless, but planning is everything”.

—Eisenhower

It’s the process of developing the project plan that is actually more useful than the documentation you generate.

Depending on your organization’s internal process and your work’s regulatory requirements, a project plan could be a barebones process, or a lot of paperwork. We would joke at NASA that you absolutely need to deliver all your paperwork...but if you happened to deliver the hardware, that would be nice too.

If you are new to project planning methods, consider implementing only what is truly necessary for your organization so that the project planning process becomes a useful tool and not a burden. Come chat with us for more details on how to implement this.

A word or warning to organizations just starting project management: If your company does not have a project management approach and just started thinking it would be a good idea, and you are the first project manager, be prepared for the worst. Why? Because in spite of the importance of project planning, a project manager appears to do pointless paperwork, doesn’t generate hardware, and harasses people with deadlines. It appears the project manager is not contributing and serves to annoy people who are doing “real” work. And since the role is new no one knows what you’re supposed to be doing, your work likely won’t be valued. To ensure success, make sure you have support from your management, and management is vocal about sending the message down the chain that what you are doing is essential (and real work).

Some keys to successful project planning

Scope out your project and project goals

What’s involved? What is the scope and the objectives? What are the risks and how do you plan on mitigating them? If this is an R&D project, and there’s a chance the hardware won’t work, is that a successful end point, or do you need to simultaneously explore multiple avenues to avoid a bad surprise? Above all, clearly identify what “DONE” looks like for this project.

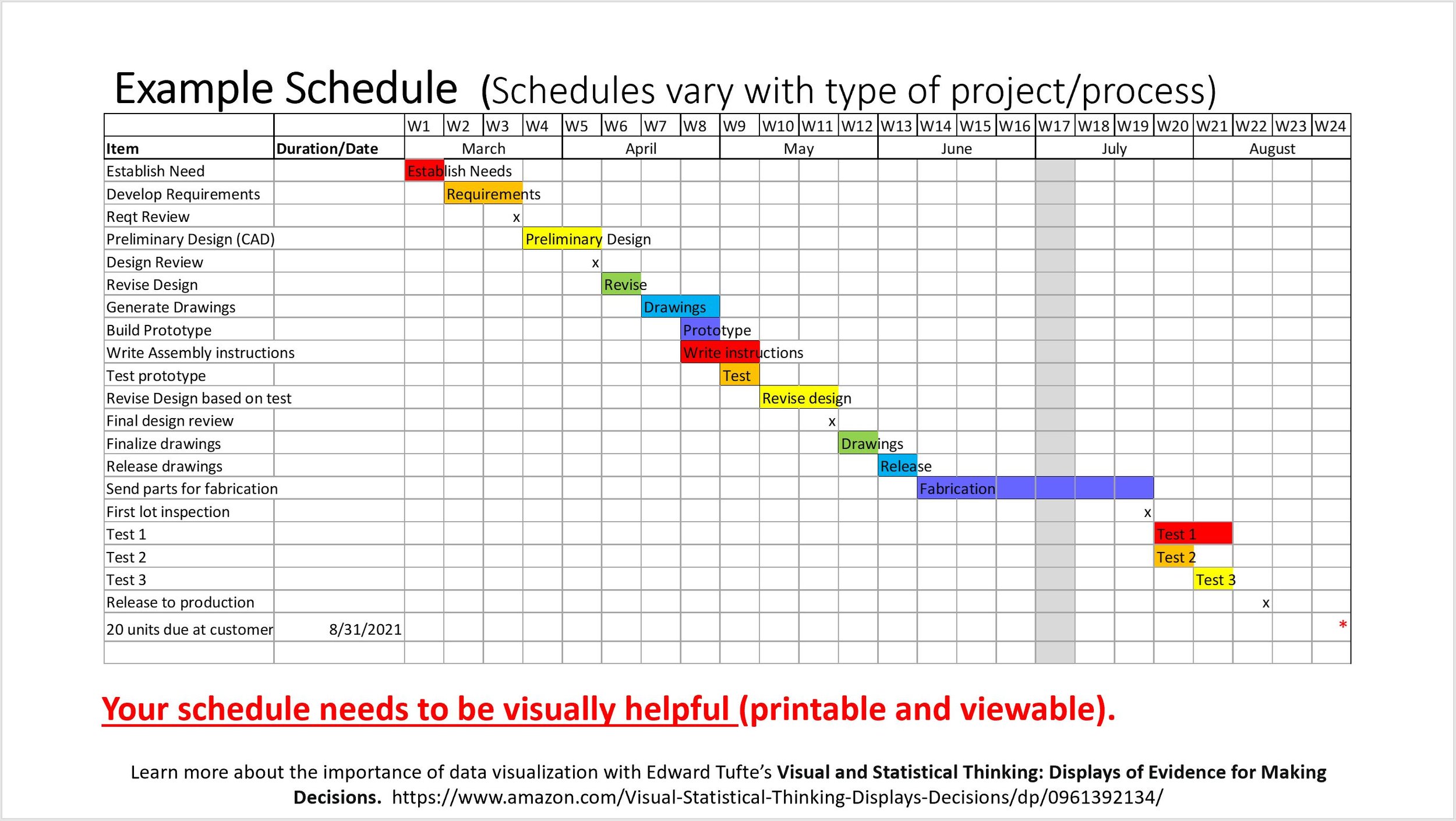

Start with schedule and plan forward.

List the steps and time that might be involved in each step (when you know). Each step should be concrete, and achievable by a single agent (engineer, machine shop, testing house, shipping department, etc.). Identify those agents as you go. Some things will be easier than others to predict. You can contact potential vendors for lead time estimates. Estimating engineering design time is the hardest part, unless you are making something that you’ve done before. Reviewing past projects for ACTUAL engineering development schedule can sometimes, but not always, be helpful. Don’t forget to include validation or testing throughout and at the end. This can be a very long process (sometimes 1/4-1/3 of project schedule).

ALWAYS ASSUME THE WORST for schedule, cost, mass, etc.

It’s 6-20 weeks for connectors? You better bet it will be 20 weeks. If your company has a drawing or document release process, plan in the worst case review and release time. If big design reviews are required, and it will take you 2 weeks to throw them together, plan in that time. If your management doesn’t like the schedule hit, remind them they could just have fewer design reviews). Remember that project management takes time and therefore is an item in your project plan (yes, it’s self referential). Above all, be honest, and stick to it.

Add margin.

Remember that uncertainty, whether in schedule, mass, or cost, is always higher at the beginning of a project, and ideally decreases as you progress. I once worked with someone who recommended multiplying schedules by pi. You want to be Star Trek’s Mr. Scott, who always had just enough time left to fix the ship, because he secretly always had schedule margin in his time estimates. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0708764/

Confirm that you have the staffing (FTE’s or full time equivalents).

Make sure your schedule estimate lines up week by week with the correct number of staff, with the right skills, and that their time is actually available. Needing Bob for 2 FTE in October isn’t likely going to mean that Bob will be available, interested, or productive enough to produce 2 people’s worth of work. If you need production manufacturing support, make sure they have buy in on your schedule, and they pencil you in on theirs. If you are dealing with technicians or operators, remember that a technician day may be as short as 6.5 hrs, given the number of required breaks. Talk to your technicians about how they estimate available time per day. (This is not to assume that engineers are any more effective with their time).

My plan is broken! What do I do now? It’s entirely possible that you go through the full planning exercise and find out that the target schedule, cost, mass, risk, etc. just aren't going to work. (Mars and launch windows aren’t going to wait for you just because you’re not done with a rover on time). What do you do then? This is where you pull out the objectives from your plan, ramk them, and start the difficult discussion about descoping. Identify what is absolutely necessary, and what may be worth trading for schedule, cost, risk, or whatever your fixed constraint(s) are. This is generally a very difficult decision, and one that is made in collaboration with the project manager, technical stakeholders, and other management. The results may be a descoped task with less features, the customer accepting a longer schedule, a request for new funds, or realization that maybe the project isn’t feasible at this time. Remember that it’s better to figure this out at the beginning, than years down the road, with dollars spent.

Need help with your project’s unique parameters? Contact us.